Connecting the Inner Life with the Outer Life

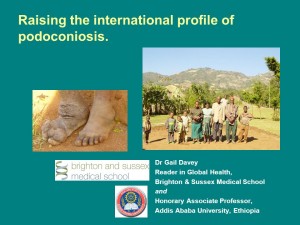

A conversation with Dr. Gail Davey, PhD, Founder

Footwork: The International Podoconiosis Initiative

David: Thank you very much, Gail, for joining me in a conversation about compassion and global health. As way of an introduction, I’m interested in the connection between our inner life—which one might call “spiritual,” or a “life of faith,” or the “humanistic or altruistic impulse”—and our outer life, particularly the work that we do. I wonder why is it that these two lives, the inner and outer, can tend to be so far apart. How does your own inner life, or spiritual life, influence your work in podoconiosis and your approach to doing this work?

Gail: I believe that aligning with something bigger than what we do day-to-day is important. I am a Christian, and I feel a time of quietness and prayer is really valuable each day. This time helps to shape how things unfold for me throughout my day and throughout my life. Some people are able to look back on their life and find that their outer life has come together in a way that makes sense, that there has been a shape to their experiences. This has happened to me and has affected the direction I’ve taken with my work. My inner life, my spiritual life, informs me that something larger than me had a hand in this.

Gail: I believe that aligning with something bigger than what we do day-to-day is important. I am a Christian, and I feel a time of quietness and prayer is really valuable each day. This time helps to shape how things unfold for me throughout my day and throughout my life. Some people are able to look back on their life and find that their outer life has come together in a way that makes sense, that there has been a shape to their experiences. This has happened to me and has affected the direction I’ve taken with my work. My inner life, my spiritual life, informs me that something larger than me had a hand in this.

Having a sense of something bigger puts everything in perspective for me, and it’s enabled me to take more risks at times. Knowing that all is well, even if I mess up, has been important. This belief has enabled my husband and me to take risks at particular stages in our lives, more than many would have been prepared to do. These risks included moving to a less-developed country (Ethiopia), taking voluntary positions, and then discovering what this meant for us. I feel very fortunate that I was able to do that. It gave me the  opportunity to develop ideas and to see personally what was needed in Ethiopia. If I had gone with a particular agenda or a funded research project, as many people advised me, I might never have come across the work that has now seized my life. I’m glad of that.

opportunity to develop ideas and to see personally what was needed in Ethiopia. If I had gone with a particular agenda or a funded research project, as many people advised me, I might never have come across the work that has now seized my life. I’m glad of that.

The other thing that’s shaped my enjoyment and desire to continue working in the field of podoconiosis has been my sense of social justice. To live justly and show mercy, those are two ideals for many faiths. They certainly speak to me daily, and have informed my work so far.

David: In public health, a lot of what we do is “mechanical.” It’s about providing resources, or delivering supplies, or, in your work with podoconiosis, figuring out the right kind of shoes that are needed and distributing them. The work can be programmatic and systematic. I think that one of the challenges in global health is the disconnect between one’s spiritual impulse to serve (the inner life) and the actual day-to-day practice of implementing that service (the outer life). In other words, the means through which compassion or love are expressed may be very mechanical and programmatic. How can one infuse that very linear public health mechanical thinking with the kind of life force that comes out of spiritual desire? How do you nurture the inner life when the outer life moves in a regimented way, comprised of design studies and spreadsheets?

Gail: Keeping the end goal in mind helps. It is that of serving people. Even though you may be involved in task-oriented projects, there are people who are part of that work. We need to be organized and systematic about things, but we also get to relate to people all the time. This is crucial. It is people we’re designing shoes for, or it’s people who have to know how much is left in the budget for the project. Looking relationally at these processes is fundamental.

Gail: Keeping the end goal in mind helps. It is that of serving people. Even though you may be involved in task-oriented projects, there are people who are part of that work. We need to be organized and systematic about things, but we also get to relate to people all the time. This is crucial. It is people we’re designing shoes for, or it’s people who have to know how much is left in the budget for the project. Looking relationally at these processes is fundamental.

The area of podoconiosis requires work in development as much as it does in epidemiology or public health. I recently heard someone describe development as a “chain of trust,” and that seemed to me a very apt description of what has happened to the human side of the science I’m involved in. Those chains of trust are vital, and the chains include organizations, too, so I feel mechanical and spiritual work can coexist.

David: I like your comment about the relational aspect of this.

Gail: Yes, understanding relationship is particularly important when you move into another cultural setting, because relationships may work in a different way in another country. That certainly was true in Ethiopia. There, you get very little done if you call people on the phone. You must go and sit with them. Just this one small example has deepened my understanding of the importance of relating to people.

David: In global health, the structures of our work can challenge our ability to relate to those we are working for. We work for people that we may not meet, or people who are not yet born. The doctor or nurse in a burn unit has the face of suffering right in front of them. The challenge in such situations is to not over-identify with the patient’s suffering, so that you can maintain the connection to the patient but not be consumed by personal distress. In global health, the problem is reversed. We are often sitting in our offices analyzing data, looking at spreadsheets, and reminding ourselves about the suffering people and populations we are hoping to help. There is no direct face-to-face connection. Our outer life work no longer has the stimulus of direct connection with another human being, which often feeds the inner life. How does one sustain a sense of connection with the relational aspects of the work when trying to improve population health?

Gail: I suppose I’m probably luckier than many in global health. I’m still doing fieldwork, so three or four times a year I’m in Ethiopia or Cameroon with people and patients in the field. I’m engaged in face-to-face activities such as training community workers. I have immediate contact and I’m sure that sustains me through those long days when I was in front of a computer back in my office.

Gail: I suppose I’m probably luckier than many in global health. I’m still doing fieldwork, so three or four times a year I’m in Ethiopia or Cameroon with people and patients in the field. I’m engaged in face-to-face activities such as training community workers. I have immediate contact and I’m sure that sustains me through those long days when I was in front of a computer back in my office.

David: Is it challenging to move between compassion for the individual and for the collective? You seem to do this in your work. You are providing shoes to one person or a community of people, and you are also creating a global program. You are thinking in terms of global scale and yet your connection and what feeds you relationally in this work is the ongoing connection and contact with individuals. Sometimes when we move onto the global population level, we lose the personal connection that fuels our work.

Some of us who work in global health try to get to the field as often as we can to keep those connections alive and feed our inner life. We return to the office refreshed with a renewed, positive attitude because we’ve experienced what sustains us. Are their spiritual rituals or ceremonies you engage to maintain your inner life once you return to the office? Are you able to talk about spirituality and compassion with colleagues?

Gail: Very good questions. When I was on sabbatical in Ethiopia under the auspices of the International Orthodox Christian Charities, we discussed different models for the podoconiosis program related to the different faith settings within Ethiopia. Within this context, faith was absolutely overt, so it was fine to bring spirituality and compassion into the conversation. Now I look to create spaces and build systems so that I can have these conversations regularly, and I engage with people who understand my work situation and encourage and support me. That was important in Ethiopia, and it is here as well. It is crucial to create structures and spaces that motivate you to carry on your work so that your inner life and your outer life remain connected.

Dr. Gail Davey, a medical epidemiologist who has worked on podoconiosis since 2002, is Footwork’s founder. Prof. Davey coordinates international research teams investigating disease distribution, genetic and mineral causes, disease pathogenesis, social and economic consequences, clinical and community management, and behavioural interventions to improve prevention. She is advisor to NaPAN, the Ethiopian National Podoconiosis Action Network, and the WHO’s Department of Neglected Tropical Disease Control.