Motivated by Compassion

by Bill Foege, MD, MPH

At a meeting for one of the boards I used to sit on, the president of the faculty, who was completing his three-year term, was giving us a report. He said he had taken the job out of necessity. He thought it was something that he needed to do, but then he found out he actually liked doing it. He said, “I asked my wife ‘would you in your wildest dreams have thought I would enjoy doing something like this?’” His wife replied, “I don’t want to disappoint you, but you’ve never figured into my wildest dreams.”

At a meeting for one of the boards I used to sit on, the president of the faculty, who was completing his three-year term, was giving us a report. He said he had taken the job out of necessity. He thought it was something that he needed to do, but then he found out he actually liked doing it. He said, “I asked my wife ‘would you in your wildest dreams have thought I would enjoy doing something like this?’” His wife replied, “I don’t want to disappoint you, but you’ve never figured into my wildest dreams.”

Our wildest dreams are to see global health equity, and compassion plays a key role in this. I remember when I was looking for a cancer surgeon. I was looking for great skill, an ego so large that he or she couldn’t bear to lose, but I was not looking for compassion. By chance, I found out afterwards what motivated this talented surgeon… it was compassion.

Over the years as I hired people in the global health field, I sought the same sort of ego, one that was so strong it could not accept failure. Indeed, these people were skilled and ambitious, yet I continually discovered that global health employees had something else, too. They reminded me of the Peace Corps volunteers I worked with in the early 1960’s. I also saw similarities to the campus radicals of the same time period, and the strong sense of social justice that informed their talk, desires, and plans. Their passion and work for the underprivileged and disenfranchised were guided by a life philosophy and the ability to relate to suffering, not just the results of certain skills or knowledge.

Later, my understanding of why global health people were different became clear. I used to say to students that the purpose of science is to find truth, to break down the walls of ignorance; the purpose of medicine is to use that truth for every patient; but the philosophy behind public health, global health, is to use that knowledge, that truth, for everyone. Therefore, social justice becomes the basis for public health. It’s no wonder it attracts people with social justice interests. Compassion is not a substitute for skills, knowledge, or technical ability, but it often provides the motivation.

My thirteen-year-old grandson has added a tagline to his email that says, “I dream of a future where a chicken can cross the road without having its motivations questioned.” Likewise, I try to focus on the results of people in public health without questioning their motives. However, I end up hoping for workers in global health who have empathy and a shared sense of the suffering of others. This will help them make the right decisions. This empathy, this compassion, is exactly what I want in a teacher for myself or for my children. It is what I want when I look for mentors. It is part of what holds society together. Compassion is not just an attribute for global health workers, but rather one needed by all of society. And, the presence or absence of compassion has consequences.

Independence Hall in Philadelphia is very inspiring. Our founding fathers were obviously applying compassion beyond their time, attempting to develop a system that would be fair to all people in the future. For all of their individual failings, they were willing to share the suffering of the disenfranchised and show compassion for current and future generations. Perhaps they were able to imagine a time when many of their successors might become fixated on their own self-interest and the desire to become elected. In viewing Wall Street and Congress, I get a glimpse of what happens in our society when compassion is overcome by self-centeredness. Even in our medical field I recall when the American Medical Association was so concerned about socialism creeping into medicine that they never saw the encroaching threat of capitalism. The threat of capitalism is far greater than the threat of socialism. Now our healthcare system is far more expensive per capita than any other on earth, but not even ranked among the top ten globally in terms of health outcomes. Compassion is often eclipsed by the selfishness of the marketplace, unseated by profit as the bottom line.

At the same time, find compassion in unexpected places. We have corporations that exhibit compassion. Who expected Merck to donate at no cost over a half-billion treatments for river blindness? Or GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Pfizer, and others who gave billions of dollars of medication for global programs? I’m amazed by the GSK announcement by CEO Witty that he would sell malaria vaccine at 5% over cost and that GSK would use that 5% profit for research in neglected diseases. Who would have expected that? Corporate compassion is not something we were taught to expect.

At the same time, find compassion in unexpected places. We have corporations that exhibit compassion. Who expected Merck to donate at no cost over a half-billion treatments for river blindness? Or GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Pfizer, and others who gave billions of dollars of medication for global programs? I’m amazed by the GSK announcement by CEO Witty that he would sell malaria vaccine at 5% over cost and that GSK would use that 5% profit for research in neglected diseases. Who would have expected that? Corporate compassion is not something we were taught to expect.

I end my segment with three major lessons. First, compassion is the glue that holds society together; global health is not a unique home. Compassion is the motivation behind social improvement, concern about the future, action to prevent global warming, and nuclear arms talks. When the forces of compassion are silenced by the greedy, we suffer greatly in finance, politics, and healthcare. Second, some of the most compassionate forces within global health are the corporations that we have been taught to vilify. Third, it’s not compassion itself we need to measure but rather the results of compassion. As Desmond Tutu said, “frequently people think of compassion and love as merely sentimental. No! They are very demanding. If you are going to be compassionate, be prepared for action.”

The bottom-line of compassion: global health is inclusive of health everywhere, including the health of people in Philadelphia. Our targets, strategies, and tactics continue to change, but our objectives remain the same. We are still trying to reduce premature mortality; we’re still trying to get rid of unnecessary suffering or morbidity; and we’re still trying to improve the quality of life and the bill of health that are often due to social determinants: poverty, illiteracy, gender bias, unemployment, homelessness, depression, violence, alcohol, drug dependence, fatalism.

Grizzly bears are able to stay sociable when they are fishing salmon out of the river by never looking each other in the eye. The animal-behavioral specialists say that if the bears actually made eye contact, there would be a confrontation. Well, compassion encourages people to make eye contact, to inspire confrontation, and to want to improve the human condition. Therefore, those interested in global health are interested in increasing compassion for all of society and improvements for everyone.

Thank you.

(This talk was given at the The Impact of Compassion in Global Health and Tropical Medicine, ASTMH Symposium in Philadelphia, December, 2011.)

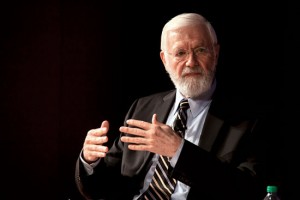

William H. Foege, M.D., MPH, is a Senior Advisor for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. He is an epidemiologist who worked in the successful campaign to eradicate smallpox in the 1970s. Dr. Foege became Chief of the CDC Smallpox Eradication Program, and was appointed director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control in 1977. In 1984, Foege and several colleagues formed the Task Force for Child Survival, a working group for the World Health Organization, UNICEF, The World Bank, the United Nations Development Program, and the Rockefeller Foundation. Its success in accelerating childhood immunization led to an expansion of its mandate in 1991 to include other issues which diminish the quality of life for children. Dr. Foege joined The Carter Center in 1986 as its Executive Director, Fellow for Health Policy and Executive Director of Global 2000. In January 1997, he joined the faculty of Emory University, where he is Presidential Distinguished Professor of International Health at the Rollins School of Public Health. In September 1999, Dr. Foege became a Senior Medical Advisor for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Dr. Foege is the recipient of many awards, holds honorary degrees from numerous institutions, and was named a Fellow of the London School of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 1997. He is the author of more than 125 professional publications.