Alleviating Suffering: Disease Prevention, Treatment, and Elimination

A Conversation with LeAnne Fox

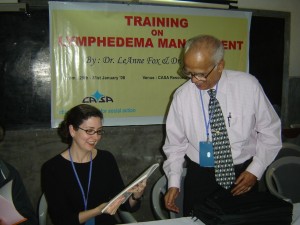

Lead, Elimination and Control Team, Parasitic Diseases Branch, CDC

Julie: LeAnne, I am excited to learn from you today about your work in neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and the role that compassion plays, particularly in addressing the suffering caused by lymphatic filariasis (LF). Let’s begin – what inspired you to enter the field of global health?

LeAnne: Early on, even before high school, I was interested in medicine. I was fascinated by the area of infectious diseases, which aims to develop and administer treatments to cure people of disease. That said, I almost left medical school after the first two years. I took a leave of absence and completed a Masters of Public Health at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health where my eyes were awakened to the field of global health. I met colleagues and professors who were doing what I aspired to do.

It’s also where I learned about the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which I subsequently completed later in my career. I was able to return to medical school with renewed energy and vision about where I wanted to make a contribution. This has sustained me through medical school, residency, fellowship, and now working in global health at CDC.

It’s also where I learned about the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which I subsequently completed later in my career. I was able to return to medical school with renewed energy and vision about where I wanted to make a contribution. This has sustained me through medical school, residency, fellowship, and now working in global health at CDC.

Julie: You have dedicated much of your career at CDC to studying LF and finding effective treatment for the stigmatizing condition known as lymphedema or elephantiasis. What has motivated this passion?

LeAnne: I’m a pediatric infectious diseases doctor by training with an interest in global health/tropical diseases. I came to CDC for the EIS program in 2002 and was interested in many of the infectious disease programs. Parasitic diseases piqued my interest the most, as (like many infectious diseases physicians in the US) I had learned very little about them in medical school, residency or fellowship. It represented a steep but fascinating learning curve. Lymphatic filariasis (LF) is one of the most prevalent parasitic diseases in the world with 1.4 billion (over one–seventh) of the world’s population at risk. It’s also a parasite that was determined by the International Task Force for Disease Eradication to be eligible for global elimination. I had become excited about global disease elimination during my time at Johns Hopkins when I met Dr. D.A. Henderson and learned the story of smallpox eradication. I think one can’t help but be moved when you see pictures of people affected by LF – people with large swollen legs or groins (for men). The opportunity to contribute to creating a world where no one will suffer from this disease in the future was very exciting for me.

When I am working with individuals with lymphedema and elephantiasis, I see compassion in global health firsthand. People with LF who have swollen legs oftentimes feel isolated and stigmatized by their communities. In addition, it is hard for them to stand, walk, and work. They are at risk for and suffer greatly from secondary bacterial infections of their legs which ultimately makes the lymphedema worse. Over 40% of the global burden of LF is in India, where at least 1 million people have lymphedema. In my role at CDC, I’ve been assisting the national Indian LF elimination program and also an NGO in India that has trained thousands of volunteers and health care workers to provide home–based care to individuals with lymphedema and elephantiasis.

When I am working with individuals with lymphedema and elephantiasis, I see compassion in global health firsthand. People with LF who have swollen legs oftentimes feel isolated and stigmatized by their communities. In addition, it is hard for them to stand, walk, and work. They are at risk for and suffer greatly from secondary bacterial infections of their legs which ultimately makes the lymphedema worse. Over 40% of the global burden of LF is in India, where at least 1 million people have lymphedema. In my role at CDC, I’ve been assisting the national Indian LF elimination program and also an NGO in India that has trained thousands of volunteers and health care workers to provide home–based care to individuals with lymphedema and elephantiasis.

Julie: What motivates the hundreds of volunteers and community workers who bring treatment to these patients?

LeAnne: The volunteers have numerous stories of people with lymphedema who are shunned by their families and communities. The family doesn’t allow the lymphedema patient to eat with them, the parents don’t allow the grandchildren to see the grandparent with lymphedema, in some cases young girls have been placed in isolation in their homes because their lymphedema is considered shameful to the family. It is transformative for a family and a village when a volunteer seeks out the lymphedema patients, touches and washes their legs, and takes time to listen to them and teach them how to care for their legs.

Volunteers also work with the family to teach them to assist the patient as well. It is particularly impactful when it crosses religious (or caste) boundaries. For example, in the program I assist, we have many examples of a Christian volunteer washing the leg/foot of a Hindu or Muslim patient and vice versa. The volunteers and community workers receive a lot of gratitude from the patients. When they come back to check in on patients and their families, they are received with open arms. It’s really wonderful for them. They have told me that patients will say “you did not see me for two weeks and I missed you.” Their services are really needed and appreciated by the patients.

Volunteers also work with the family to teach them to assist the patient as well. It is particularly impactful when it crosses religious (or caste) boundaries. For example, in the program I assist, we have many examples of a Christian volunteer washing the leg/foot of a Hindu or Muslim patient and vice versa. The volunteers and community workers receive a lot of gratitude from the patients. When they come back to check in on patients and their families, they are received with open arms. It’s really wonderful for them. They have told me that patients will say “you did not see me for two weeks and I missed you.” Their services are really needed and appreciated by the patients.

Julie: Who in your life awakened this sense of compassion in you?

LeAnne: My parents are very compassionate people. My father spent a few years in college and then was drafted and served as a naval aviator. My mother didn’t have the opportunity to attend college, although she is incredibly smart. Both my parents began working at very young ages to support their families. I think I understood at a young age how fortunate I was – with two loving parents, my needs taken care of, and wonderful educational opportunities. I grew up with the philosophy “to whom much is given, much is expected.” I was raised in a small town in New England, which, at that time, was not racially or socioeconomically diverse. My church community, which included faculty from Yale University, helped open my eyes to a broader world and the many needs, both local and global. My father became a commercial airline pilot after he left the Navy and that opened my world view as well.

Also, compassion is fundamental to global health. If we define compassion as “to suffer with,” “to have empathy for,” or “to work to alleviate suffering,” that is the basis of what we do in global health – we prevent suffering by preventing disease, and alleviate suffering through care and treatment of disease. Compassion speaks to our common humanity. We are all vulnerable to disease and don’t want anyone to suffer from something that can be prevented or treated. I do work that improves the health status of people on a global level.

Julie: The World Health Organization (WHO) strategic plan for LF notes that the morbidity management component of the LF program is “rooted in compassion.” Why do you think WHO gave this label to morbidity management rather than to interrupting transmission of the LF parasite?

LeAnne: Morbidity management (which is what we call the care and treatment for lymphedema/ elephantiasis and hydrocele) has historically been the ‘neglected’ pillar of the LF elimination program and a ‘neglected’ part of the NTD programs. We are resource constrained and that is difficult when you see that the global needs are so great. It is estimated that 40 million people suffer from lymphedema/ elephantiasis and hydrocele globally. That said, this situation inspires and requires us to be very creative and innovative and to integrate well with other programs. Morbidity management speaks to strengthening health systems. These care and treatment programs reside in primary and tertiary health facilities as well as through the efforts of community health workers.

Morbidity management for LF is the essence of “alleviating suffering” because the suffering is so apparent in the afflicted patient. Lymphedema and elephantiasis are chronic conditions and they require consistent care. That is a difficult concept at times for an elimination program that focuses on interrupting transmission of the LF parasite and being done. Creating a world where no one develops lymphedema/ elephantiasis or hydrocele due to LF infection, by interrupting LF transmission, also has a basis in compassion, but since LF infection is clinically asymptomatic in many, the precept of “alleviating suffering” really speaks to the care and treatment aspect of morbidity management.

Morbidity management for LF is the essence of “alleviating suffering” because the suffering is so apparent in the afflicted patient. Lymphedema and elephantiasis are chronic conditions and they require consistent care. That is a difficult concept at times for an elimination program that focuses on interrupting transmission of the LF parasite and being done. Creating a world where no one develops lymphedema/ elephantiasis or hydrocele due to LF infection, by interrupting LF transmission, also has a basis in compassion, but since LF infection is clinically asymptomatic in many, the precept of “alleviating suffering” really speaks to the care and treatment aspect of morbidity management.

Julie: What does compassion ask of us as we consider transmission interruption vs morbidity management – preventing disease in future generation’s vs caring for those who now suffer from disease and disability?

LeAnne: Compassion asks that we balance these two principals carefully. We need to do them both. For example, we have shown in India that when morbidity management services are provided to afflicted populations (there are >17,000 lymphedema / elephantiasis patients in the district where we work), people are much more willing to take the yearly mass drug administration (MDA) to eliminate LF transmission. These two “pillars” of the LF program benefit from each other. There has been a lot of emphasis on scaling up MDA to interrupt LF transmission, which is appropriate, but as we begin to work to scale down these MDA programs, we cannot forget the patients. The patients are the ones who motivated us to start the program to begin with and we need to make sure there are services in place for their care after the MDA component of the program ends.

Julie: You work in a large, powerful institution. How does one keep the flame of compassion alive in such a setting?

LeAnne: That’s a good question. I’m privileged and grateful to work at the CDC. Although the NTD and LF portfolio of work is a small component of CDC’s Global Health program, we are doing important and impactful work and collaborate well with the many partners in the NTD field. CDC has amazing people and a wealth of technical expertise on so many fronts – disease prevention, surveillance, epidemiology, and laboratory, etc. I have a great team of medical officers, epidemiologists, public health advisors, laboratory researchers, fellows, students, and many others, who are passionate about NTDs and who continue to persevere in our work.

LeAnne: That’s a good question. I’m privileged and grateful to work at the CDC. Although the NTD and LF portfolio of work is a small component of CDC’s Global Health program, we are doing important and impactful work and collaborate well with the many partners in the NTD field. CDC has amazing people and a wealth of technical expertise on so many fronts – disease prevention, surveillance, epidemiology, and laboratory, etc. I have a great team of medical officers, epidemiologists, public health advisors, laboratory researchers, fellows, students, and many others, who are passionate about NTDs and who continue to persevere in our work.

Julie: What sustains you and gives your work meaning?

LeAnne: I’m sustained by the people whom I am helping and the wonderful people with whom I am working, both in-country and at CDC. I’m rejuvenated when I am in the field and working with patients, field personnel, and program managers and I see the positive impact of the program. When a lymphedema patient states that their legs feel better, they are back at work, haven’t had any bacterial infections of their legs, and they are better accepted in their community, it is wonderful to know I’ve had a part in that process. Also, when my science and publications provide the evidence for national and global policy changes, that is another very positive feeling, because I know that the impact of my ability to relieve suffering has just grown. These patients are so grateful for any assistance we can give, it is definitely motivating. I’ve also been so fortunate to have great mentors along the way. David Addiss and Patrick Lammie, amongst others, have supported my work in LF and particularly on morbidity management. I’m very grateful to have had these opportunities.

Also, I really enjoy mentoring students and fellows. The NTD field is fairly young, so it’s rewarding to mentor the next generation of NTD experts. Our global NTD goals are quite ambitious and there is a lot of work to do globally. I enjoy introducing students to the field, seeing their enthusiasm, and supporting them in working in NTDs.

There may be many times in one’s career (particularly when you are concentrating on passing an exam or doing statistics homework or slogging through a tough medical rotation) when you will wonder how is anything I am doing now going to relate to what I really want to do in global health? Am I just wasting my time (or my money)? It’s a valid question and I’ve asked myself that a lot, too. One thing to remember is that you are building skill sets that will be important for the work you want to do, even if you are not doing it yet. Another important aspect is to take time to nurture your passions, whether through community or individually. It is important not to lose sight of why you have chosen a global health career, to spend time with others who share your passions, and to nurture your feelings of compassion, which are likely somewhere near or at the core of this decision.

Julie: How has your career in global health benefited your children?

LeAnne: My children are young (although getting older!), so they have not yet travelled with me to the countries where I work on NTDs. They have met several of my international colleagues from India, Haiti, and several countries in Africa. I think having a career in global health has made the world seem smaller for my children. We have a big map at home and they know where I travel and they have seen lots of pictures from the trips (they love it when I am flying a ‘far’ distance on the map!). I do believe they are developing the understanding that they are very fortunate – they have food, water, clothes, education, health care – and not all children in the world have those things. I hope this will translate into them making compassion a central component of their work in the future, too.

LeAnne: My children are young (although getting older!), so they have not yet travelled with me to the countries where I work on NTDs. They have met several of my international colleagues from India, Haiti, and several countries in Africa. I think having a career in global health has made the world seem smaller for my children. We have a big map at home and they know where I travel and they have seen lots of pictures from the trips (they love it when I am flying a ‘far’ distance on the map!). I do believe they are developing the understanding that they are very fortunate – they have food, water, clothes, education, health care – and not all children in the world have those things. I hope this will translate into them making compassion a central component of their work in the future, too.

Dr. LeAnne Fox, MD, MPH, DTM&H is presently the Lead for the Elimination and Control Team in the Parasitic Diseases Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The focus of her work is on global neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). Her research interests include lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis) and soil-transmitted helminthiasis (intestinal worms) as well as child pneumonia. LeAnne has authored and coauthored over 40 scientific papers and book chapters and has mentored approximately two dozen fellows, EIS officers, medical residents and graduate students over the past several years. She serves on a World Health Organization (WHO) Working Group for lymphatic filariasis, chairs the Filariasis Scientific Program Committee for the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) and is Associate Editor for the journal, Pathogens and Global Health. LeAnne is a Commander in the US Public Health Service. She lives in Atlanta, GA with her husband and two children.

Dr. LeAnne Fox, MD, MPH, DTM&H is presently the Lead for the Elimination and Control Team in the Parasitic Diseases Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The focus of her work is on global neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). Her research interests include lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis) and soil-transmitted helminthiasis (intestinal worms) as well as child pneumonia. LeAnne has authored and coauthored over 40 scientific papers and book chapters and has mentored approximately two dozen fellows, EIS officers, medical residents and graduate students over the past several years. She serves on a World Health Organization (WHO) Working Group for lymphatic filariasis, chairs the Filariasis Scientific Program Committee for the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) and is Associate Editor for the journal, Pathogens and Global Health. LeAnne is a Commander in the US Public Health Service. She lives in Atlanta, GA with her husband and two children.