Compassion, Bearing Witness, and Global Health

By David Addiss, MD, MPH

Those who take refuge in the Zen Peacemaker Order vow to live a life of engaged spirituality, guided by three tenets: Not knowing, giving up fixed ideas about oneself and the universe; bearing witness to the joy and suffering of the world; and compassionate action, healing oneself and others.

Although global health practitioners are generally not familiar with the three tenets per se, the principles embodied by the tenets are central to sound global health practice. Not knowing is essential for planning, developing, or implementing any new intervention. All global health students are taught the unfortunate consequences and wasted resources associated with “solutions” to health problems, devised in North America or Europe, and “taken to the field” with no local input. The most significant advances in global health are made by those who have intentionally practiced not knowing – spending long periods of time or living with the communities they seek to serve, with no preconceptions, and responding to the direction of the community.

Although global health practitioners are generally not familiar with the three tenets per se, the principles embodied by the tenets are central to sound global health practice. Not knowing is essential for planning, developing, or implementing any new intervention. All global health students are taught the unfortunate consequences and wasted resources associated with “solutions” to health problems, devised in North America or Europe, and “taken to the field” with no local input. The most significant advances in global health are made by those who have intentionally practiced not knowing – spending long periods of time or living with the communities they seek to serve, with no preconceptions, and responding to the direction of the community.

This is exemplified by Drs Abhay and Rani Bang, physicians educated at Johns Hopkins University, who returned to rural Gadchiroli, India, to establish the Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health. They moved to this impoverished, underserved area and listened deeply, not knowing, to the community as it explored and eventually articulated its own health needs. The priorities for all of their pioneering and highly influential health research are established by the community, not by the Bangs’ own research interests or those of external agencies.

This is exemplified by Drs Abhay and Rani Bang, physicians educated at Johns Hopkins University, who returned to rural Gadchiroli, India, to establish the Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health. They moved to this impoverished, underserved area and listened deeply, not knowing, to the community as it explored and eventually articulated its own health needs. The priorities for all of their pioneering and highly influential health research are established by the community, not by the Bangs’ own research interests or those of external agencies.

The development of community-directed treatment with ivermectin is another example of the application of not knowing in global health. When ivermectin became available to treat isolated rural communities throughout West and Central Africa for onchocerciasis, an inexpensive, sustainable approach was needed. The practice of not knowing, of listening deeply to community needs, led to the development of community-directed treatment, in which the community – not an international agency or even a national government – decides if the community will participate, who will distribute ivermectin to the community, when treatment will occur, how many distributors will be trained, and whether they will receive monetary compensation. Not knowing also has contributed to several major advances in global health, made by dedicated young people who either ignored or were uninformed that what they were attempting was “impossible.”

One does not often hear the phrase “bearing witness” in global health circles; to many in global health, it has a rather passive ring, inconsistent with the active, problem-solving orientation of global health. Yet, at a May 20, 2013 conference in Atlanta on global health and hunger, Tom Frieden, the Director of CDC, said that “one of the major roles of public health is to bear witness.” Intrigued by his use of this phrase, I wrote to Dr Frieden, formerly the Health Commissioner of New York City, to ask if he was familiar with Bernie Glassman. He was not. As a public health leader, Dr Frieden recognizes the power of bearing witness to shine a light on health inequities, to express and nurture solidarity with those who suffer, and to mobilize resources to transform that suffering.

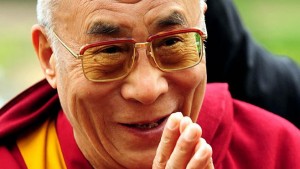

Global health also is deeply concerned with compassionate action. His Holiness the Dalai Lama has colorfully highlighted the importance of action, saying that compassion “is not just a wish to see sentient beings free from suffering, but an immediate need to intervene and actively engage, to try to help…According to Buddhist thinking, if a person who has attained stability in his or her compassion training continues to stay in seclusion, that person is not really doing anything with compassion. That person should now be out, running around like a mad dog, actively engaged in acts of compassion.”

Global health also is deeply concerned with compassionate action. His Holiness the Dalai Lama has colorfully highlighted the importance of action, saying that compassion “is not just a wish to see sentient beings free from suffering, but an immediate need to intervene and actively engage, to try to help…According to Buddhist thinking, if a person who has attained stability in his or her compassion training continues to stay in seclusion, that person is not really doing anything with compassion. That person should now be out, running around like a mad dog, actively engaged in acts of compassion.”

Global health practitioners tend to place too great an emphasis on the “action” part of compassionate action, on a frenetic effort to heal “the world” without an understanding or awareness of their own inner suffering. When global health leaders met at The Carter Center in 2010, the term “consequential compassion” was suggested to distinguish it from compassion not linked to action. This term resonated with those who were present, and it may be a useful vehicle for bringing compassion into global health discourse.

However, compassion does not cling to a particular outcome. One is compassionate regardless of whether one’s compassionate act is “consequential.” The compassion of Mother Teresa for the poor and the dying of Calcutta was arguably of little consequence as measured by indicators typically used in global health. In addition, the term “consequential compassion” implies that one can gauge the veracity of compassion by a measurable outcome. In 2012, Jack Templeton, President and  Chairman of the John Templeton Foundation, pointedly asked me, “If compassion has to be consequential, does the dedicated work of those working on a malaria vaccine, which eventually proves to be ineffective, not qualify as compassionate?” Finally, compassion may be most needed, and most difficult, when nothing “consequential” can be done. In such settings, compassionate presence may be much more important than “compassionate action.” Indeed, compassionate end-of-life care has little to do with consequences and everything to do with presence.

Chairman of the John Templeton Foundation, pointedly asked me, “If compassion has to be consequential, does the dedicated work of those working on a malaria vaccine, which eventually proves to be ineffective, not qualify as compassionate?” Finally, compassion may be most needed, and most difficult, when nothing “consequential” can be done. In such settings, compassionate presence may be much more important than “compassionate action.” Indeed, compassionate end-of-life care has little to do with consequences and everything to do with presence.

(This is an excerpt from an article published on Upaya’s Zen Center website.)